How I understand the Syrian revolution

On January 26th 2012 I participated in a BBC College of Journalism panel discussion on Syria. The attendance consisted of senior BBC journalists and broadcasters, some of whom are household names in the UK. What they were looking for was a nuanced understanding of what is happening in Syria from experts, which goes beyond the superficial and the cliche.

On the panel was Dr Fawaz Gerges of the LSE, who offered his own reading of the situation. Then it was my turn. This is what I had to say:

I looked at the Syrian revolution from a historian’s perspective and asked myself: how would historians in 30-40 years’ time explain the remarkable events that we are now witnessing? It is difficult to make those kind of judgements without the benefit of hindsight, but I had a go.

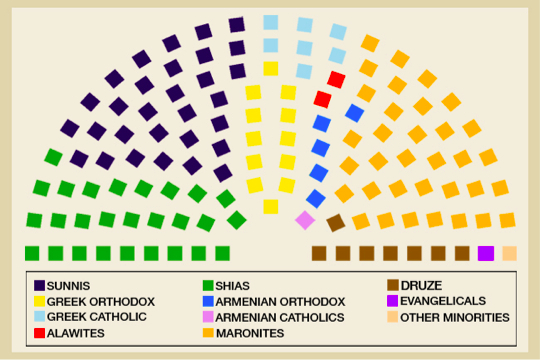

My reading is that the Syrian revolution is the revolution of the rural Sunni working classes against the Alawite-dominated military elite and the urban bourgeoisie (both Muslim and Christian) that has profited from the Assad dictatorship.

I make the case that the Syrian opposition, itself an elite group, albeit political/intellectual, is almost as fearful of the revolution as the regime itself because of the wide-sweeping social change that will follow a collapse of the status quo. That is why its role in the revolution is more mediator than leader.

Genuine democracy in Syria will usher in a new elite that will give political expression to disenfranchised sections of society, who in turn, will transform the nature and identity of the Syrian state. This is why regime loyalists (and some within the Syrian opposition intelligentsia) find the revolution to be so dangerous.

The collapse of the regime may not come soon because the social groups that represent the backbone of Assad’s Syria are still cohesive and believe in the Assad regime’s ability to survive. It is not so much belief in Bashar Al-Assad as blind faith in the system.

However, if Assad falls, it will be as a result of regional and international consensus on the need to remove him from power. That consensus has not yet been reached, and it may never be reached.

Keeping the system or ditching it is a separate question all together. Assad’s Syria without Assad is a scenario currently being floated by the political opposition and the west.

The success of the Syrian revolution is not a foregone conclusion. The regime is bolstered by Iran and Russia, and indirectly, by Israel’s better-the-devil-you-know attitude. It is also encouraged by the west’s reluctance to commit to military intervention – quite possibly the only effective deterrent that Assad will take seriously.

A lot will depend on Syrians’ ability to organize themselves and speak with one voice. The signs so far are not encouraging. The political opposition has not been able to offer a convincing narrative of what the Syrian revolution is about and what kind of Syria they wish to create. Simply saying that it is a revolution for democracy and human rights is not enough – the question is: whose democracy and whose human rights?

This may all sound too academic but unfortunately, this is what it takes to truly understand the Byzantine nature of Syrian politics and society. In other words, to make sense of the Syrian revolution.

Syria’s revolution has yet to capture the world’s imagination

It may sound cruel but over the past few weeks Syria’s pro-democracy revolutionaries have been pushing and shoving for headline space with their Libyan and Yemeni counterparts. It’s not hard to see why. Getting the West interested in your particular revolution is a sure way of maximizing the potential for its success, for every Arab knows that the US and the EU who have long accepted dictators as a fact of life (and therefore legitimized them) can de-legitimize them with a press conference or two. Getting the Western media to talk about your revolution will lead to public pressure, which leads to leaders making statements, paving the way for policies to be formulated and political pressure exerted.

The Libyans have so far received the lion’s share of interest. To be fair, they did get in first when they sparked their uprising against Gaddafi back in mid-February. Their column inches is impressive, if not the present course of their revolution which has stalled on the battlefields of Brega and Ras Lanuf.

The Yemenis have so far followed the rather more peaceful Egyptian model, remarkable given the amount of weaponry in ordinary citizen’s hands. However, lack of economic incentives, the relatively low number of dead and injured and the real threat of Al-Qa’ida has made the Western media somewhat wary of embracing the Yemeni revolution. In many ways its a less “sexier” revolution than Libya’s: there’s no Dr Evil-type villain, no African mercenaries, no perfect Mediterranean backdrops, no oil fields; just thousands of Yemenis in traditional garb squatting in the centre of the capital San’a.

The Syrian revolution took everyone by surprise. I say everyone; some did foretell what was to come but these voices were drowned out by the well-informed experts who assured us that the Syrian regime was ‘immune.’ How the mighty have fallen. The problem as far as the Syrian revolutionaries are concerned was that their timing was awful. By mid-March the Western media was enthralled by the images of NATO jets taking off on bombing runs in Libya, and terrified by the threat of nuclear meltdown in Japan; both stories easily relegated Syria to the back pages.

Not for long though. Hundreds of protesters turned into thousands, and inevitably, dozens of dead and injured. Syria is at the crossroads of converging political interests; it is a police state par excellence run by a militarized mafioso family; it’s beauty and romance tempered by undercurrents of danger and extremism. The world just had to take notice.

Take notice it did; the problem was that the debate was being framed within the context of reform, not revolution. This has meant that news editors are giving Syria less attention that it deserves. In part this is the fault of the protesters themselves who initially went out onto the streets demanding reform, not regime change. The media as a whole however, Arab and Western, did not pick up on the subtleties of Syrian doublespeak, which inevitably develops in a totalitarian dictatorship of 48 years. When Syrians say they want “change”, they mean regime change, not just a change in the law, and when they talk about “freedom” they mean freedom not to be ruled by the Assads. The culture of fear still permeates Syrian society, and many still prefer to skirt on the edges of the hated “red lines” rather than dare cross them. All this has meant that there is a great deal of confusion as to the real aims of the revolution. The body count is there, but not the clarity of purpose.

In Tunisia it took several weeks for the protests to solidify into a popular, coherent and nationwide anti-Ben Ali uprising. Syria will take longer; the adversary is more sophisticated and considerably more brutal. If the protests continue, which they will, and Libya-fatigue begins to set in, Syria will feature more prominently in newspapers and on news channels. Glad tidings for the revolution as it seeks to find its deserved place in the media limelight.

On Sky News: World’s attention needs to focus on Syria

Sky News called me this morning and asked if I would comment on what has been happening in Syria these last few days. Understandably, I jumped at the opportunity. As far as 24-hour rolling news networks go, Sky News is a big player, and for them to take an active interest in Syria when Libya and Japan have been dominating the headlines must surely be applauded and encouraged.

That got me interested in Sky News’ take on Syria so I started following their hourly news bulletins. To my pleasant surprise, I found their foreign affairs editor Tim Marshall’s take on Syria refreshingly frank and to the point. He understood the Sunni/Alawi issue and he correctly noted that Syria was the most repressive Arab dictatorship out there (that’s right, not Saudi!) Dr Omar Ashour of Exeter University was also there in the studio and he offered an incisive look at the nature of Middle Eastern dictatorships. I found it all very interesting so well done Sky News team.

At around 6:40pm it was my turn to appear live on Sky News as a “spokesman for the opposition.” I am nothing of the kind of course, but there is a saying in Syria: “Better to be known as a rich man than a poor man”. Here’s how the interview went:

I tried to convey two important messages in what little time I had. One was that Syria is the one to watch because regime change there will have widespread regional repercussions, more so than Yemen or Libya. The second message was related to the situation in Dar’a which is critical given the very real risk of massacres by the army and security forces that were descending upon the city in frightening numbers.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to get hold of a good quality recording. The best I could manage was this mobile phone footage from my niece who watched the interview on her laptop. It’s not even the whole interview but you get the idea.

If any of you were wondering, that comfortable-looking chair I’m slouched on is a POÄNG armchair from Ikea, available for £90.90.