Out of the Ashes: My review of the first authoritative history of the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria

Published: 13 March 2013

Syria was the first modern Arab state to come into existence and the first Arab republic to elect its president, and it had the first Arab army to procure arms from the Soviet Union. Syria was also the first Arab democracy to elect an Islamist to parliament (Mustapha Al-Sibai in 1947), and the first Arab dictatorship to witness an armed jihadist insurrection (waged by the Fighting Vanguard, 1975–1982).

Syria, then, has something of the pioneering spirit; where its elites have led, other Arabs have tended to follow. This is especially true of the Islamists, whose journey from the ballot box to violent insurrection, and now seemingly back to the ballot box once again after the Arab Spring, appears largely to have been foreshadowed in the story of one organization in particular: the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. It therefore came as something of a bittersweet irony for me, a Syrian, to learn that the first authoritative political history of that organization was written by a young Frenchman at Cambridge University.

That is not to take away anything from Raphaël Lefèvre, who, in his encouraging first book Ashes of Hama: The Perilous History of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood, seeks to bridge the considerable gap in the knowledge of the Syrian Brotherhood’s ideological evolution and internal politics without resort to partial sources. In the process, he has written a work of tremendous importance to anyone seeking a nuanced understanding of the dynamics driving the revolution in Syria, whose violent and sectarian turn has left many looking for answers.

Unlike many of the offerings of late, this book on Syria has not been written hastily, lazily or politically. Lefèvre comes across as a scholar with a delicate appreciation for continuity in an area of the world where history moves slowly. He correctly identifies the origins of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood in the Salafi movement of 1860s Damascus, where a number of reformist religious scholars attempted a selective revival of Ibn Taymiyyah’s thought.

Ibn Taymiyyah was a pioneer in his own right, and he was ‘Syrian’ inasmuch as he was an influential theologian of fourteenth-century Damascus. Although he is not considered progressive today, his ideas nonetheless provided the intellectual ammunition for many reformist movements within Islam that sought to confront the challenges of European domination through fundamentalism. Whether in the Salafi movement of the Najd, theIkhwan (Brotherhood) of Egypt, the Sanusia of North Africa, or the contemporary worldwide jihadist current, Ibn Taymiyyah’s ideas on what it means to be a “real” Muslim were hugely influential.

In Syria, this brand of revivalist Islam accommodated for democracy when the elites that championed it were able to play the parliamentary game. Once the country slipped under Ba’athist dictatorship, however, those elites had to find alternative arenas to probe and challenge. With an eye firmly set on the present, Lefèvre reminds the reader of the formative impact of Syria’s first (and failed) Islamist ‘revolution’ of the late 1970s and early 1980s, which in turn profoundly shaped the Syrian government’s attitude to the current one. Sectarian strife, regionalism, class struggle, the fragmentation of the army, and the jihadist phenomena: all these have their antecedents in Syria’s not-so-distant past.

Ashes of Hama, then, is a sophisticated study that treats the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria less as a local franchise of a global brand and more as an organic expression of a largely middle-class and urban Sunni conservatism. Relying on a large number of first-hand interviews and the memoirs of key players, Lefèvre charts the Brotherhood’s rise from humble and relatively moderate beginnings to becoming the Syrian government’s most dangerous enemy, membership in which is still punishable by death. It is a voyage into the murky underbelly of an organization where truth and rhetoric are difficult to prize apart, and where codes of silence and a culture of opacity has made Lefèvre all the more enterprising.

Where the book is letdown is where Arabic words have been misspelt, or where there are gaps in the knowledge. For instance, the social and ideological roots of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Hama and Aleppo factions are dealt with superficially, and there is no mention of the negotiations that took place in 1979 between Brotherhood leaders and Hafez Al-Assad prior to their declaration of an all-out jihad that same year.

These, however, are minor oversights that take little away from a book that is highly readable, well researched, and long overdue. As a study it breaks new ground; my only wish is that it had been written by a Syrian.

“Dead at 21: Britain’s Veteran Jihadist”: My first report for the Sunday Times

Published: 3 March 2013.

http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/uk_news/National/Terrorism/article1224370.ece

My op-ed for Syria Deeply: Talking About My Generation

It is said that the Arab revolutions are the revolutions of the young. Statistically at least, this is true.

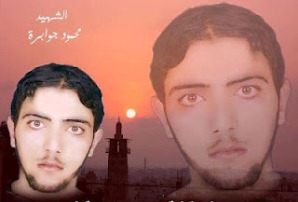

The first martyr in Syria, Mahmud Qteish al-Jawabra [left], was a teenager, and the symbol of the revolution, Hamza al-Khatib, was a 13-year old tortured to death. According to this database, 70 percent of the revolution’s martyrs are under the age of 30.

Whether it be citizen journalism phenomena, or tansiqiyat protest-organizing committees, or massive online campaigns, these were all made by young people.

What al-Jawabra and al-Khatib stand for is not only the revolution itself, but also for the demographic that made it happen. So why is it that when it comes to political leadership of the revolution, it is left to middle-aged men in bad suits?

The median age of a member of the SNC executive committee is 56, more than quarter of a century shy of the median age of the fighters and activists who are carrying out the revolution on the ground.

While the term “Arab Spring” denotes something new and fresh, revolutionary leadership in Syria has seen the return of many of the old faces: Muslim Brotherhood, al-Qaeda, assorted Salafists and ex-Communists and a sprinkling of balding generals.

Perhaps this is to be expected in a paternalistic society where young people are expected to remain reverential, and where matters of importance are decided by a family’s older members.

Given the level of physical and moral sacrifice made by the young, however, this is no time to submit to tradition.

Revolution is about challenging hierarchies of power, wealth and authority. It’s not just about writing slogans and posting YouTube videos. Setting up a human rights abuse documentation center or helping out in the relief effort does not equate to a political program.

Too often, Syria’s youth have mistaken day-to-day activism for revolutionary politics. This has led to an atomized movement that lacks clear intellectual direction.

In order for Syria’s youth to take back ownership of the “their” revolution, they need to change the way they view themselves.

More energy should be focused on promoting “demographic consciousness,” an understanding of Syrian politics that regards the 18-35 age bracket as a distinct political constituency that is above sect, ethnicity and class.

While the politicians are busy jockeying for position, there is now an opportunity for the youth to formulate an agenda of their own – one that puts their interests above all others.

Young martyrs have talked about the pent-up frustrations that led so many of Syria’s young people to take a stand against the existing regime.

Why then are the sources of these frustrations not being addressed? Where is the guaranteed funding pledge for education? Where is the commitment to investment in the IT and new media industries, at which younger Syrians excel?

Why are there no demands for a minimum wage for young workers face exploitation? Why has no one addressed the problem of military conscription? And why is there no talk of a guaranteed quota for young people in a future parliament?

The lack of young political leaders to give voice is worrying.

The focus should be on the future, and what it will look like depends much on the youth who will set to inherit political power in the decades to come.

They will have an opportunity to shape their country in their own image rather than that of their parents, but for that to happen they should begin to entertain collective political ambition.

http://beta.syriadeeply.org/op-eds/2013/02/talking-generation/#.US4qJB3wmyY

Blogging for the Majalla on Jordan: The King is Listening

Published: 29 January 2013

The recent elections in Jordan, held amidst a boycott by the main opposition parties, have fuelled talk of a missed opportunity. The argument goes that a toothless parliament, composed mostly of loyalists elected by an unfair electoral system, will be unlikely to provide a legal and democratic channel for dissent, leaving the opposition no option but to resort to the street.

Indeed, recent protests over price hikes have led some observers to speculate that Jordanians have grown wary of the king and are, like their neighbors to the north, ready for an uprising. Others concede that a full-blown uprising is unlikely, but that sweeping political reforms are urgently needed to avoid serious instability in the future. The side that advocates reform has, by and large, dominated the debate on Jordan.

But does King Abdullah II really need to reform so quickly and so deeply? A little-publicized incident from the northern town of Ramtha suggests that he can afford to take his time. In November 2011, twenty-year-old taxi driver Najm Al-Azayza was arrested by Jordanian military police on suspicion of smuggling arms across the nearby border with Syria. After four days in custody, the family of the young man were informed that he had “hung himself,” and were instructed to collect his body from the local mortuary. What followed was a riot that saw the Amman–Damascus highway closed and a police station and municipality building burned to the ground. The clan to which the young man belonged demanded justice, accusing the authorities of torturing their son to death.

What followed could so easily have been a re-run of events in Dera’a, Syria. Eight months earlier, similar circumstances in that city involving police brutality resulted in a nationwide uprising that continues to this day. Instead, Awn Al-Khasawna, then prime minister of Jordan, intervened and ordered an immediate investigation by the country’s chief coroner. When that failed to pacify the townsmen, it fell to King Abdullah II to settle the matter in person. The officer accused of the torture was arrested, compensation was promised and calm restored to the town.

While acts of royal magnanimity alone may not be enough to stave off future internal instability, they do underscore a number of key lessons that Jordan watchers will be wise to take on board. The first is that whatever mistakes agents of the state commit in their dealings with ordinary people, in Jordan the king is still seen as the ultimate guarantor of justice. That, in a clan-based society, is hugely important in affirming his legitimacy to rule over the kingdom.

The second is that the government has grown accustomed to handling outbursts of popular anger. Because Jordan is not a repressive state, and because the security forces there tend to tread lightly when compared to their neighboring counterparts, demonstrations and calls for reform are nothing new. At times, disturbances have resulted in real and immediate reforms, such as during the April 1989 food riots that led to the resumption of parliamentary politics. Most of the time, protests do not end in fatalities and local grievances are settled within the community through civil society networks. The moderation of the Jordanian political system helps to prevent sparks turning into fires.

Jordanian monarchs are not stubbornly resistant to change, but they are resistant to change where significant challenges to their authority exist. Given the civil war in Syria, the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and growing instability in Iraq, it would seem uncharacteristically enterprising for the Jordanian monarch to embark on a program of deep political reform at this time.

King Abdullah II can take heart from the fact that the demands of recent protests have been mainly economic, and that the Islamist-dominated opposition remains weak and splintered. Despite high fuel prices, the Jordanian middle class does not object to subsidy reform as long as it is offset by greater inward investment. There is still some ground to cover in the war against high-level corruption, but with the conviction last year of the former head of the intelligence directorate, it appears that a serious start has been made. The impression in Amman is that the king will deliver reform at a pace congruous with wider developments in the region, but at least he is listening.

Latest for The Majalla: Mr. Öcalan’s Philosophy

Mr. Öcalan’s Philosophy

Syria’s Kurds learn lessons from the architect of Kurdish self-determination

8th January 2013

Across a narrow belt of land along Syria’s northern border, Kurds are staking a claim to self-determination. Where the overstretched Syrian army withdrew voluntarily in July last year, People’s Protection Units (YPG) fighters have moved in, setting up checkpoints and raising the yellow, red, and green flag of Western Kurdistan.

In towns such as Kobai, Amuda, Efrin, Al-Malikiyah, Ra’s Al-’Ayn, Al-Darbasiyah, and Al-Ma’bada, it is the Kurdish Supreme Committee that provides local government. The body was formed in July 2012 when the two main Kurdish factions in Syria, the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and the Kurdish National Council (KNC), agreed to run Syrian Kurdistan together. Today, popular committees are effectively responsible for providing everything from security to meeting residents’ food and energy needs. Local elections have been held, Kurdish language schools have opened, and loud political rallies have passed off without incident where once they would have ended in almost-certain arrest.

Qamishli and Hasake remain the only cities in the Kurdish-majority area where regime security forces maintain a presence—but even in those, alongside pictures and statues of the Assads that remain intact, Kurds now enjoy levels of political and cultural freedoms unparalleled by those they had during fifty years of Ba’ath Party rule. Uniquely for Kurdish peoples in the region, these freedoms have been won at relatively little cost to Kurdish life and property. It is a remarkable turnaround for a people whose own rebellion in March 2004 was brutally suppressed, and many of whose members were denied Syrian citizenship as recently as last year.

The decision to reverse the findings of the 1962 census and offer nationality rights to an estimated three hundred thousand Kurds, made by Bashar Al-Assad soon after the outbreak of the uprising, was dismissed by the Arab opposition as a bribe. It may well have been. Syria’s Kurds do not endorse Assad’s brutal crackdown, but neither have they offered wholehearted support to the Arab opposition. Instead, they appear to have steered a cautious middle course, guided by Kurdish national interests.

How those interests are defined is the primary concern of the Syrian franchise of the Kurdish Worker’s Party (PKK), the separatist militant organization that has waged war against Turkey’s military since 1978. It has set up the PYD in Syria, and this affiliate is at the center of the Kurdish quest to capitalize on the growing weakness of central government control, more than any other party. Its strategy is informed by the PKK’s experiences in Turkey, where concessions have been won through a combination of military pressure and—more importantly—political organization.

The PYD aims not to establish its own nation-state (a near impossibility in the circumstances) but to implement a form of Kurdish autonomy that can co-exist with whomever happens to rule from Damascus. It is a new path towards Kurdish autonomy—quite possibly independence in all but name—and it may just work in a fractured and war-torn Syria just as it has done in Iraq.

Democratic confederalism

“In fifty years, the Kurdish parties could not offer anything to Kurdish politics or to the Kurdish people of Western Kurdistan,” said PYD leader Salih Muslim. “We established the PYD, which is different from the classical parties in Syria. We have the philosophy of [PKK leader Abdullah] Öcalan, and his ideas are adapted to the conditions and situation of Western Kurdistan.”

Öcalan’s philosophy has undergone notable changes since his capture by Turkish agents in 1999. Most notably, he has disavowed the demand for independent Kurdish statehood, and instead calls for the adoption of a “non-state social paradigm.” In an eponymous pamphlet, loosely inspired by the European Charter of Local Self-Government, he calls his big idea democratic confederalism. “Democratic confederalism in Kurdistan aims at realizing the self-defense of the peoples by the advancement of democracy in all parts of Kurdistan without questioning the existing political borders,” he wrote from his prison cell. “The movement intends to establish federal structures in Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq that are open for all Kurds and at the same time form an umbrella confederation for all four parts of Kurdistan.”

Democratic confederalism may well be Kurdish independence through the back door. Replacing the problematic aim of cessation with a less threatening and more long-term stratagem based on demanding local political and cultural rights makes sense, but in effect it entails stripping powers away from central government and handing them over to local bodies on the periphery, run by organizations that have little or no loyalty to the nation-state. This could prove problematic for a country like Turkey.

Unperturbed, the Justice and Development Party (JDP) government of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan sought to capitalize on what it saw as increasing pragmatism on the part of the Kurds. The rise of organizations such as the Union of Communities in Kurdistan (KCK) and the Peace and Democracy Party (BDP), both of which take their cue from guiding principles of Abdullah Öcalan, have given the Kurdish struggle a more political and civic flavor.

In a sign of this changing position on Kurdish issues, prayers in Kurdish were allowed to be held for the first time in Turkey’s mosques, names of cities were changed from Turkish to their original in Kurdish and language classes were taught in schools. The JDP government even set up a state-run Kurdish language TV channel, TRT 6, and launched an initiative, the GAP Action Plan, to channel assistance and investment to the economically deprived southeast. The aim, at least as far as can be ascertained, was to build confidence in order to pave the way for a negotiated settlement with the PKK.

Seasoned observers agree that the so-called Kurdish opening, launched early in 2009, has now floundered. Despite Erdoğan’s bribes, the PKK remains active; despite peace overtures, Turkish soldiers in the southeast of the country continue to die.

If Erdoğan did not reap much reward for his efforts, the same cannot be said of the Kurds. They have come away with a renewed sense of purpose, and are now more self-assertive than ever, having expanded their nonviolent activities and built up their political capacity alongside their military one. In the June 2011 general election, the BDP increased its seats in the Turkish Parliament from 16 to 36, ensuring that the calls for autonomy are heard loud and clear in Ankara.

Young Kurds are now encouraged to work within civil society groups and umbrella organizations that dominate the Kurdish political scene, rather than just join the PKK in the mountains. By offering Kurds a route to get involved without having to risk their lives in armed struggle, the PKK has gained new adherents and respect. “The PKK has become part of the people. You can’t separate them anymore, which means if you want to solve this problem, you need to take the PKK into account,” said Zübeyde Zümrüt, co-chair of the BDP in Diyarbakir province.

New prospects in Syria

As news reports this week indicate, the Turkish government still believes in negotiating with the PKK. That, however, may well be more to do with tempering the growing power of the PKK’s sister organization in Syria, the PYD, than in any genuine desire to offer tangible concessions. Öcalan’s philosophy may still prove to be effective in wearing down the Turkish state in the long run, especially if the JDP proceeds with attempts to transform Turkey into a multi-ethnic state. In the short to medium term, however, Turkey remains too strong and too centralized to buckle under the pressure of Kurdish agitation.

Syria offers a more realistic prospect for the implementation of democratic confederalism. For a start, it is much weaker than Turkey, and contains a Kurdish minority large enough to sustain calls for autonomy. Then there is the geopolitics: as Assad gets progressively weaker, powers as divergent as Iran and the US will be courting the Kurds as a counterweight to the Sunni Islamists. Its neighbors in Iraqi Kurdistan provide a working model to emulate because the Iraqi region runs its own affairs independently of Baghdad rather well, having avoided the sectarian bloodletting that engulfed the rest of the country. There is also an energy interest, with the YPG already providing security for the smooth running of oil installations in Al-Hasakah Governorate. The fact that Syria is an artificial state whose borders were drawn by Britain and France with little attention paid to ethnic and tribal continuity is a further, historical, reason why democratic confederalism may succeed there but fail in Turkey.

But there is a simpler, more practical logic to Öcalan’s philosophy. Put simply, his adherents have delivered modestly in Turkey and spectacularly in Syria. Their organization and political acumen has enabled them to trade armed opposition for de facto autonomy, in the process sparing Kurdish towns and populations the fate of cities like of Homs and Aleppo. They have also rightly identified that to apply pressure on Ankara, a solid foothold in Syria was essential. Regardless of the outcome of the revolution, it will be unlikely that Western Kurdistan will lose self-administration rights anytime soon.

In contrast, the Arab opposition has brought death and destruction upon its towns and populations, with no guarantee of a favorable outcome or of having the necessary capacity to administer areas under its control effectively. Once the regime in Damascus collapses, it is doubtful whether the sacrifices of (predominantly) Sunni Arabs will compare favorably with the rewards that they will reap. The Kurds of Syria have taken the cash in hand and waived the rest.

My latest for The Majalla: The Monarchical Exception

The Monarchical Exception

While republican dictators fell, Arab monarchies remain stable

If there is one thing that can be said for certain about the Arab Spring, it is that monarchies have fared a lot better than republics. Opinions differ over why that is. Cultural legitimacy and institutional statecraft do make monarchies more stable than republican dictatorships. More cynical observers have cited oil security and geopolitical stability as more tangible explanations for why uprisings have not erupted in Riyadh or Rabat.

Amid this debate, there is a less perceptible factor that has been largely overlooked, and it has much to do with the way states manage popular expectations. What regimes in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Libya and Syria all had in common was that they emerged at a time of high optimism, when Arab nationalist republicanism was at the forefront of progressive politics.

At the time, Arabs believed that self-determination could only be realised by sweeping away regressive internal forces through top-down revolution and by keeping out malign foreign interference. Those were the heady days of Nasserism.

The Nasserite republic in Egypt offered countries in the region a model to be emulated. In return for surrendering certain freedoms, including the freedom to elect one’s government, a military elite guaranteed the people stability and security, as well as universal education and healthcare, cheap food and jobs for all. What was also promised was dignity. The Nasserite-type republic swore to restore Arab pride by nothing less than victory on the battlefield.

Stretching the laws of sociology and economics to breaking point, the Nasserite-type republics promised so much but delivered little. As decades dragged on, people became disillusioned with what they saw as a case of diminishing returns.

The death knell for the Nasserite-type republic came on 9th April 2003 when US forces invaded Iraq and, in swift and humiliating fashion, unseated Saddam Hussein, the ruler who more than any other took the Nasserite model to its most brutal and absurd conclusions.

But by then, similar regimes had already begun reverting to a system of government reminiscent of the ancien regimes that they had overthrown in the 1950s and 60s. Whether it be hereditary leadership or adoption of free-market capitalism, the republics began to take on the political and economic characteristics of Arab monarchies. In seeking to emulate the monarchies, however, the republics failed to adjust their people’s level of expectation.

The monarchies did not promise their people a welfare state nor to liberate Palestine nor to confront the West. The monarchies cultivated positive relations with the West, which secured foreign investment but also contributed to a partial settlement of the Palestine issue through negotiations. Even in those monarchies that didn’t have oil, standards of living were generally higher than republics with similar economies.

In many ways, the kings and emirs were more honest with their peoples inasmuch as they didn’t attempt to sell them a pipe-dream; their policies suited the social, economic and geo-political circumstances of the countries they ruled, and not much more. The cautious and conservative policies adopted by the monarchies, based on gradual and organic change, would appear to be better suited to the conditions of societies newly emergent into modernity.

The republics on the other hand maintained the rhetoric of the all-powerful, progressive state, and with it the apparatus of state repression, but they were neither able to deliver on the economic pledges that were part-and-parcel of the grand bargain, nor the military victories promised.

The republics became accustomed to raising people’s levels of expectation, and by way of their construction, could not afford to lower those expectations lest people demanded political rights. They were, in essence, trapped by a rigid and deceitful rhetoric that was wearing thin.

According to this interpretation, the monarchies did not really survive the Arab Spring since they were never in real danger of falling in the first place. Their peoples’ expectations were never that high to begin with, and so they were not judged according to a particularly harsh criterion.

When seeking to explain why republican regimes fell and monarchies didn’t, the notion that uprisings swept across the Arab World is unhelpful. The facts are that uprisings only swept across Nasserite-type republics, and it is in the failures of these types of regimes that the roots of the Arab Spring lie.

My latest article for The Majalla: So Long, Renaissance

Morsi plays a zero-sum game

Egypt’s President Morsi is going head to head with the country’s judiciary after issuing a decree severely limiting their powers to rein in the Muslim Brotherhood.

On Thursday, 22 November, Egyptian President Mohamad Morsi went to war with the judiciary. He issued a seven-point decree that included the sacking of the country’s prosecutor-general and announced that all his decisions were immune to appeal “by any way or by any entity.”

Critics have called the move a brazen power grab; admirers call it a “revolutionary decision.” Both sides will agree, however, that the announcement will only further polarize an Egyptian society struggling to reach a consensus on how to proceed after Mubarak’s fall.

The main cleavage is one of Islamists versus non-Islamists. The Egyptian president belongs to the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), the largest Islamist group, which claims that it has a popular mandate to implement the much-vaunted “renaissance project.” Ranged against him are liberals, leftists, and former regime elements entrenched in state institutions.

The Brotherhood may have won nearly half of all parliamentary seats in the November 2011 election, but the margin of Morsi’s presidential victory over his secular rival was a far more modest 51.7 percent against 48.3 percent.

Such a slim majority might not have been considered problematic had Morsi adopted a consensual style of leadership. But Morsi has favored a more aggressive, winner-takes-all approach that not only risks plunging Egypt into further turmoil, but also marks him out as a distinctly unoriginal Islamist.

Take his handling of the Constituent Assembly, the body tasked with drafting a new constitution. Having already stuffed it with his own supporters to ensure a favorable outcome—a presidential system with limited role for the legislature—it risked falling apart after prominent secular and Coptic members walked out earlier this month.

The controversy-prone body was already beset by questions over its legitimacy after the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) deemed the Islamist-majority upper and lower houses of Parliament (on whose basis the Constituent Assembly was formed) unconstitutional, albeit on a technicality.

In April 2012, the SCC again played the role of spoiler by ruling that the first Constituent Assembly was unconstitutional on the grounds of its non-inclusiveness, and was expected to pass a similar judgment on the current constituent assembly at the end of the month.

This threatened to derail the ratification of the Islamist-friendly constitution that the MB and their Salafist allies have been busy drafting; hence the fourth article of Morsi’s decree: “No judicial body can dissolve the Shura Council [upper house of Parliament] or the Constituent Assembly.”

In an address to his supporters, the Egyptian president said that his decision was meant to stop “weevils” from the former regime from blocking progress. It is true that judges at the SCC have been overly active in recent months, frustrating the drafting of a new constitution—which will pave the way for new parliamentary elections that observers expect would be won by the Islamists. That a small and unelected clique at the top of the judiciary should be disrupting Egypt’s democratic transition—and with it the MB’s consolidation of power—is a source of deep frustration for Morsi.

Egypt’s judiciary has come under criticism too from grass-roots activists, who accuse it of not doing enough to convict security personnel accused of killing protesters during last year’s uprising. In the past three months, three trials have found policemen and thugs accused of killing protesters not guilty, much to the anger of the victims’ families. The latest trial verdict was announced on 22 November, the day of Morsi’s decree. It proved to be a convenient excuse to make a move against the judges.

Had the Egyptian president stopped at replacing the Mubarak-era prosecutor-general, Abdel-Meguid Mahmoud, he might have come away with his reputation intact. The decree he issued, however, emasculated the judiciary by exempting both Morsi and bodies controlled by the MB from any judicial review for the next three months at the very least. This will give him ample time to steamroll through vital decisions on the country’s future unchecked by the judiciary.

The audacity and breadth of Morsi’s decree sit ill at ease with the limited nature of his stated goals, and his three percentage point margin of victory. It is little wonder, then, that the division-wracked secular opposition united for the first time to challenge what it describes as “Egypt’s new pharaoh.”

The protest held in Tahrir Square on 27 November against the decree drew a respectable quarter of a million people, and the secularists promised further actions in a political escalation seemingly coordinated with the country’s top judges. Egypt’s appeal courts have already gone on strike in protest at the decree, a move unlikely to promote conciliation in an unfolding constitutional civil war.

Blanket measures

Morsi’s battle with the judiciary follows a number of successful campaigns to curb the power of other bodies that threaten the MB’s rise. In recent months, editors of independent newspapers and high-ranking members of the press syndicate have decried attempts by Information Minister Salah Abdel-Maqsoud to limit their criticisms of the government.

More recently, trade unions have complained that another MB appointee, the Manpower Minister Ahmed Hassan El-Borai, was attempting to “Brotherhoodize” the unions through a presidential decree that allows the government to appoint board members of unions.

The Egyptian Brotherhood’s tendency to want to dominate and control state institutions is not out of character for the organization. Next door in Gaza, the MB faction Hamas was unable to share power with Fatah after its triumph at the ballot box in 2007. Today, Hamas is more entrenched in its antagonism to its secular rival than ever before, a fact underscored by a recent statement by Mahmud Al-Zahar, Hamas’s chief in Gaza, who said that if Palestinian President Mahmud Abbas was to visit the territory, “he would be arrested.”

Time and time again, Muslim Brotherhood organizations across the Arab word have missed opportunities to build a durable and broad-based consensus for change and reform. Whether by inexperience or design, their policies tended to deepen division and make differences more irreconcilable. Where they have bucked this trend it has been under duress, as is the case in Morocco. Critics say that this raises serious doubts over the MB’s commitment to an inclusive democratic process in which compromise and consensus are essential pre-requisites.

But the bottom line for MB leaders like Morsi is that they feel no moral duty to make concessions to those that have been part-and-parcel of a system that has victimized the group and denied them their rightful place in Egyptian politics. The fact that a former foreign minister under Mubarak, Amr Mousa, should now emerge as the MB’s most vocal critic merely serves to delegitimize the opposition in MB eyes, and renders its calls for greater inclusiveness all the more hypocritical.

Amidst these claims and counter-claims, in Egypt what appears to matter is not so much changing the rules of power than the affiliations of those who have it—and who therefore enjoys its spoils. It is a zero-sum game where enemies must be crushed and power sought and accumulated for its own sake.

Prominent MB member Ali Abdel-Fattah did not recognize the irony when he brushed aside criticisms of Morsi by citing Gamal Abdel-Nasser as an example of a president who resorted to extraordinary decrees under the pretext of defending a revolution. “As long as [Morsi] is democratically elected,” he said, “he has all the right to issue such a declaration.” Before it was secularists side-lining Islamists, now it will be the other way around.

Egypt will not go the way of Zimbabwe by having ‘one man, one vote, one time.’ Nor will it go the way of Syria, thanks to a military that has preferred to remain above the fray. But there will be more protests, more disorder and more economic loss. A badly needed USD4.8 billion loan from the IMF has already been delayed because of the most recent instability, and the Cairo stock market plummeted for a second time in a single week.

That has not put off the combatants. The Supreme Constitutional Court announced that it was going ahead with plans to rule on 2 December on whether to dissolve the MB-dominated Constituent Assembly that has drafted the new constitution. That same assembly has since approved the draft constitution, which paved the way for a referendum. The battle for Egypt’s future goes on.